Ordinarily, I would recommend a walk down the frozen surface of Omand’s Creek, the perfect antidote for these COVID-19 days of uncertainty and social-distancing. At its mid-winter best, this is a walk with some risk—crawling on ice through a steel conduit, for example—but spring is closing in, temperatures are rising and water can already be seen flowing over deteriorating ice. A walk is all but impossible till next winter.

In its place, I offer a self-isolating, fireside-and-scotch alternative: my just-published On Omand’s Creek, the eighth in the Ways To Walk series of small softcover books.

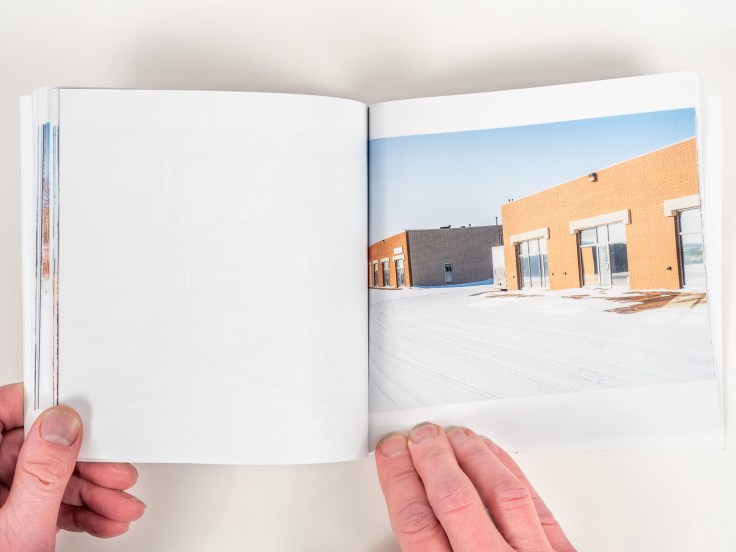

Winnipeg is blessed with frigid winters. Its rivers and creeks freeze over every year, without fail, becoming seasonal sidewalks, opportunities to revisit the city from unique perspectives. Of all those frozen waterways, Omand’s Creek is arguably the most tortured, most compromised. Yet there is an aching beauty to be seen from its white banks. On Omand’s Creek is the story in words and pictures of my trek up this iced-over creek, from its mouth at the Assiniboine River and stretching north to Brookside Cemetery.

On Omand’s Creek and the other Ways To Walk books can be previewed (in full) and/or purchased at my Blurb Bookstore.

Here’s a small excerpt from my essay for On Omand’s Creek:

There is a mechanical precision to the course of Omand’s Creek, one drawn on a drafting table in an engineer’s office rather than prescribed by the vagaries of nature. An early map, Plan of the Settlement on Red River, as it was in June 1816, shows a scraggly Catfish Creek, as it was then called, winding its way in a southeasterly direction to the Assiniboine River (or the Ossiniboyne River or Western Branch of the Red River, according to the map). Catfish Creek was later renamed Omand’s Creek, after John Omand (1823-1905), who lived near its mouth. By 1946, City maps show a much different path for Omand’s Creek. Other than having the same meeting point at the Assiniboine River, the course of Catfish Creek in 1816 is completely different from that of Omand’s Creek in 1946. Since 1946, the creek’s route has been modified even further, being aligned ever more closely to the grid of streets closing in around it.

I’m heading north on that most recent realignment. The creek is broader, a flat expanse of clean, white, deep snow. The heavy industries hang back from the gently sloped banks, giving it—and me—room to breathe. A parkland, so-to-speak, surrounded by super-scaled tin sheds, rusting machines and gantry cranes. Then the creek turns left and due west. The trail is getting tough now. The snow is deep. I can feel my thighs ache with every laboured step. In places, the bullrushes are thick, forcing me to battle my way through or give up and climb the steep bank to circumnavigate a particularly impenetrable patch. A number of bridges cross overhead. Most tunnels I can navigate, hunched over. A few are just too low. I must climb up and over.

I pass through one more steel conduit under some road I can’t identify and emerge at the edge of the James Armstrong Richardson International Airport. Or, more correctly, at the edge of a vast swath of prairie that the airport claims as its own.

What follows is a small sampling of book pages, just to get you started before heading over to my Blurb Bookstore.

Leave a Reply